Most people in Kenya, especially those living in informal settlements, consider a "normal" cough to be something they can endure and decide not to seek medical attention. They hope the cough disappears on its own, noting that seeking medical care could mean expenses they are not able to afford.

By the time they visit a hospital, the illness has often progressed to a more serious stage.

This experience reflects a wider Kenyan reality, where the cost of healthcare usually determines when and whether people seek treatment.

When Cost Dictates Health Choices

In many families in Kenya, falling sick normally triggers a financial calculation. Consultation fees, laboratory tests, medication, and transportation costs can quickly add up, particularly for low-income families.

To avoid these expenses, patients often self-medicate, rely on over-the-counter drugs, or turn to traditional remedies, a move health workers warn may seem cheaper, but they frequently delay proper diagnosis and worsen outcomes.

"Most patients come here when the disease is already advanced. By then, treatment is often more expensive and sometimes too late," says a clinical officer at a public hospital in Nairobi.

Devolution and the Push to Bring Medicine Closer to People

Following the devolution of the health sector to county governments, the national government introduced reforms that it said aimed at improving access at the grassroots.

One of the directives from the Ministry of Health was for drugs to be transported directly to dispensaries and health centres, bypassing the usual struggles that had previously delayed supplies.

The move was intended to ensure that patients could access treatment at the lowest-level facilities near their homes, reducing both transport costs and the need for referrals to larger hospitals.

Health officials say the direct delivery of medicine to dispensaries was intended to reduce shortages, alleviate congestion in referral hospitals, and encourage early treatment by making services more accessible to local communities.

Additionally, the government alleged that the traditional method of distribution fostered corruption among healthcare officials, as many officials enriched themselves.

Reality in Public Hospitals

Despite these reforms, gaps persist. Some dispensaries still experience worrying drug stock-outs, forcing patients to buy medicine from private pharmacies. For low-income families, even these "small costs" can be expensive.

Congestion, long waiting times, and understaffing in public facilities also discourage patients, particularly those who may not appear "to be "really sick. For casual workers, a hospital visit can mean a lost day of work.

"I have to work so that my family can eat. There are long queues there. If I go to the hospital simply because I am coughing, I see that as a waste of time. So I wait until the pain is too much," says a boda boda rider in Kawangware, Nairobi.

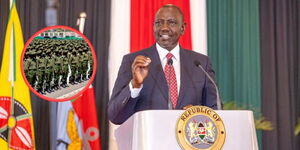

Government Intervention

To further reduce financial barriers, the government rolled out the Social Health Authority (SHA) as part of its universal health coverage agenda.

SHA was designed to expand insurance coverage, reduce out-of-pocket expenses, and ensure that every Kenyan can access essential services without struggling to afford them.

SHA targets vulnerable households, informal sector workers, and low-income earners, providing coverage for primary healthcare, emergency services, maternal care, and chronic illness management. The goal, according to the government, is to make cost less of a deciding factor when seeking treatment.

Progress

While SHA has reduced the burden for some patients, others report challenges, including unclear benefit packages and limited coverage for specialised care and chronic diseases like cancer. Some healthcare facilities are still adjusting to the new system, which is affecting the delivery of services.

Challenges

In rural areas, distance remains a primary obstacle.

Even with medicine delivered to local dispensaries, some health facilities are far away, and transport costs can limit access.

Informal sector workers also struggle with regular contributions, despite government efforts to make enrollment flexible.

Medical experts warn that delaying treatment increases both health risks and financial strain.

Common conditions such as infections, hypertension, and diabetes become more complicated and more expensive to manage when diagnosed late.

Quiet Crisis in Kenyan Homes

Behind the reforms and statistics, many are still forced to borrow money, sell their source of pride, such as livestock and land, or rely on fundraisers for medical care situations that government interventions aim to prevent but have not yet removed entirely.

As the government continues to refine devolved healthcare, expand SHA, and strengthen medicine delivery to local facilities, the challenge remains ensuring these interventions translate into timely care so that Kenyans can seek treatment early, not when it is too late.